Congleton

| Congleton | |

|---|---|

Congleton Town Hall, completed 1866 | |

Location within Cheshire | |

| Population | 30,015 (2021 Census)[1][failed verification] |

| OS grid reference | SJ854628 |

| Civil parish |

|

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | CONGLETON |

| Postcode district | CW12 |

| Dialling code | 01260 |

| Police | Cheshire |

| Fire | Cheshire |

| Ambulance | North West |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | www |

Congleton is a market town and civil parish in the unitary authority of Cheshire East in Cheshire, England. It is on the River Dane, 21 miles (34 km) south of Manchester and 13 miles (21 km) north of Stoke on Trent. At the 2021 census, it had a population of 30,015.[1][failed verification]

Toponymy

[edit]The town's name is of unknown origin. The first recorded reference to it was in 1282, when it was spelt Congelton. The element Congle might relate to the old Norse kang meaning a bend, followed by the Old English element tun meaning settlement.[2]

History

[edit]The first settlements in the Congleton area were Neolithic. Stone Age and Bronze Age artefacts have been found in the town.[3] Congleton was once thought to have been a Roman settlement, although there is no archaeological or documentary evidence to support this. Congleton became a market town after Vikings destroyed nearby Davenport.

Godwin, Earl of Wessex held the town in the Saxon period. The town is mentioned in the Domesday Book,[4] where it is listed as Cogeltone: Bigot de Loges. William the Conqueror granted the whole of Cheshire to his nephew the Earl of Chester who constructed several fortifications including the town's castle in 1208. In the 13th century, Congleton belonged to the de Lacy family.[3] Henry de Lacy, 3rd Earl of Lincoln granted the town its first charter in 1272, enabling it to hold fairs and markets, elect a mayor and ale taster, have a merchant guild and behead known criminals.[3]

In 1451, the River Dane flooded, destroying a number of buildings, the town's mill and a wooden bridge.[3] The river was diverted, and the town was rebuilt on higher ground.

Congleton became known in the 1620s when bear-baiting and cockfighting were popular sports.[3][5] The town was unable to attract large crowds to its bear-baiting contests and lacked the money to pay for a new, more aggressive bear. A legend tells that Congleton spent the money they were going to spend on a bible on a bear; this legend is only partly true as only part of the fund to buy a new bible was used to buy a new bear.[5] The legend earned Congleton the nickname Beartown. The chorus of 20th-century folk song "Congleton Bear",[6] by folk artist John Tams,[7] runs:

- Congleton Rare, Congleton Rare

- Sold the Bible to buy a bear.

During the Civil War, former mayor and lawyer John Bradshaw became president of the court which sent Charles I to his execution in 1649. His signature as Attorney General was the first on the king's death warrant.[3] A plaque on Bradshaw House in Lawton Street commemorates him. Almost opposite the town hall, the White Lion public house bears a blue plaque, placed by the Congleton Civic Society, which reads: "The White Lion, built 16–17th century. Said to have housed the attorney's office where John Bradshaw, regicide, served his articles."[8]

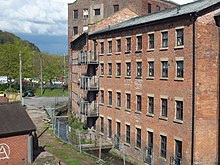

King Edward I granted permission to build a mill. Congleton became an important centre of textile production, especially leather gloves and lace.[3] Congleton had an early silk throwing mill, the Old Mill built by John Clayton and Nathaniel Pattison in 1753.[9] More mills followed, and cotton was also spun. The town's prosperity depended on tariffs imposed on imported silk. When tariffs were removed in the 1860s, the empty mills were converted to fustian cutting. A limited silk ribbon weaving industry survived into the 20th century, and woven labels were still produced in the 1990s. Many mills survive as industrial or residential units.[10]

In 1881, in order to improve the water supply to the town, a pumping station was built on Forge Lane to draw water from the springs in Forge Wood and pump it up to a water tower at the top of the hill. The red and yellow brick water tower was designed by the engineer William Blackshaw. A second adjacent tower was constructed later.[11][12][13]

Congleton Town Hall was designed in the Gothic style by Edward William Godwin. It was completed in 1866.[14]

The current hospital in Congleton was opened by the Duke of York on 22 May 1924.[15]

In 1920 , the Marie Hall home for boys was established in West House, an 18th-century house on West Road, as a branch of the National Children’s Home. It became an approved school in 1935 and was renamed Danesford School. It was converted into a Community Home with Education in 1973, run jointly by NCH and Cheshire County Council. Danesford has since closed, and the Grade II listed buildings have been converted for residential use.[16][17]

Congleton elected its first Lady Mayor in November 1945.[18]

During the celebration marking 700 years of Congleton's Charter in 1972 Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip visited Congleton in May, this was the first visit by a reigning monarch since the visit of King George V and Queen Mary in 1913.[19]

In 1983 Princess Michael of Kent visited Congleton.[20]

During the celebration marking 700 years of Mayoralty in Congleton in 2018 the Prince of Wales and the Duchess of Cornwall visited the town.[21]

In 2019 the serial rapist Joseph Mccann was arrested on a country lane in Congleton after a nationwide manhunt for him.[22]

As part of the celebration marking 750 years of Congleton's charter Congleton appointed an Ale Taster.[23][24]

In 2023 part of the Congleton town centre was regenerated as part of the Congleton Market Quarter project.[25] The regenerated part of Congleton town centre is named the "Congleton Market Quarter" and opened in November 2023.[26]. Another phase of expansion for the "Congleton Market Quarter" was announced in December 2024, and due for completion in March 2025.[27]

On 28 September 2024 Congleton appointed its first female town crier.[28]

Governance

[edit]The Congleton parliamentary constituency is a county constituency represented in the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It includes the towns of Congleton, Alsager, Holmes Chapel, and Sandbach. It elects one Member of Parliament (MP) by the first-past-the-post system of election. The current MP is Sarah Russell of the Labour Party, the previous incumbent was Fiona Bruce of the Conservative Party.[29]

Congleton forms the central portion of the Cheshire East unitary authority, located in the south-east of Cheshire. Before the abolition of Cheshire County Council on 1 April 2009, Congleton had borough status (originally conferred in 1272). The neighbouring urban district of Buglawton was incorporated into Congleton borough in 1936. From 1974 to 2009, Congleton borough covered much of south-east Cheshire.

For representation on Cheshire East Council, Congleton was divided into two wards returning three members, Congleton East and Congleton West. Three of the six seats are currently represented by Conservative Party Councillors, with one Liberal Democrat and two Independents.[30]

The town has an elected Town Council[31] which was established in 1980. The town is split into two wards with 20 councillors elected every 4 years.

Geography

[edit]

Mossley is sometimes classed as the wealthier part of town. Hightown is located in Mossley. West Heath is an estate built in the early 1960s to the early 1980s. Lower Heath lies to the north of the town. There is also the town centre.[32]

Congleton is in the valley of the River Dane. South of the town lies an expanse of green space known locally as Priesty Fields which forms a green corridor right into the heart of the town – a rare feature in English towns. Folklore says that Priesty Fields gained its name as there was no priest performing services within the town. The nearest priest was based at the nearby village of Astbury. It is told that the priest would walk along an ancient medieval pathway which ran between the fields at the Parish Church in Astbury and St Peter's Church in Congleton.[33]

Economy

[edit]The principal industries in Congleton include the manufacture of airbags and golf balls. There are light engineering factories near the town and sand extraction occurs on the Cheshire Plain.[34]

One of the most prominent industries during the nineteenth century onwards was Berisfords Ribbons, established in 1858.[35] It was founded by Charles Berisford and his brothers Francis and William. The brothers leased part of Victoria Mill, on Foundry Bank, owning the entire factory by 1872. By 1898, the company had offices in London, Manchester, Leeds and Bristol.

Congleton Market operates every Tuesday and Saturday from the Bridestones Centre.

Until about 2000, Super Crystalate balls, made of crystalate, were manufactured by The Composition Billiard Ball Company in Congleton. The company was then sold by its owner to Saluc S.A., the Belgian manufacturer of Aramith Balls. The name Super Crystalate was retained, but the manufacturing process was integrated into the standard process used for Aramith balls.[36][37]

Culture

[edit]

The National Trust Tudor house Little Moreton Hall is 4 miles (6.4 km) south-west of the town.[38]

Congleton Park is located along the banks of the River Dane, just north-east of the town centre. Town Wood, on the northern edge of the park, is a Grade A Site of Biological Interest and contains many nationally important plants.[citation needed] Congleton Paddling Pool was built in the 1930s and is open in the summer months. Astbury Mere Country Park lies just to the south-west of the town centre, on the site of a former sand quarry.[39][40] The lake is used for fishing and sailing and, despite its name, is actually in the West Heath area of Congleton, with the boundary between Congleton and Newbold Astbury parishes lying further to the south.

The independently run 300 seat Daneside Theatre is on Park Road.[41] The 400-seat Clonter Opera Theatre is based in the village of Swettenham Heath, 5 mi (8 km) north of Congleton. Founded in 1971, Congleton Choral Society is a mixed voice choir which regularly performs choral works at Congleton Town Hall and other venues around the town.

Congleton Museum is on Market Square, in the centre of town. It was established in 2002 and is dedicated to Congleton's industrial history. It also contains an ancient log boat and gold and silver coin hoards.[42] Congleton Tourist Information Centre is on the town's High Street.

The town annually hosts a food and drink festival,[43] which promotes locally sourced produce/cuisine, with a jazz and blues festival which showcases acts from across the UK. In 2019, Congleton held its first annual pride event.[44]

Congleton hosts two annual musical festivals, Congleton Jazz and Blues and Congleton Unplugged.[45]

The town once hosted the Congleton Carnival a one-day carnival which was hosted once every two years.[46] In the past the carnival was regarded as one of the best local carnivals in England, and used to last for up to three days and feature floats and live music among another attractions.[47]

For six months in summer 2011 Congleton hosted an event called "Bearmania",[48] in which over sixty 5-foot fibreglass sculptures where placed around the town.[49] Over 26,000 people came to see the bears during "Bearmania".[48]

Media

[edit]There is one weekly local newspaper: the locally owned and financed Congleton Chronicle. The evening newspaper The Sentinel, based in Stoke-on-Trent, also covers the town although less so than in the past. Local radio is broadcast from nearby Macclesfield-based Silk Radio, Hits Radio Staffordshire & Cheshire and Greatest Hits Radio Staffordshire & Cheshire from Stoke-on-Trent and BBC Radio Stoke. Community radio is provided by Moorlands Radio in Leek and Canalside Community Radio in Bollington.

Local news and television programmes are provided by BBC North West and ITV Granada. Television signals are received from the Winter Hill and the local relay transmitters.[50][51]

Congleton did have its own community radio station Beartown FM,[52] but this has now closed. There is an internet-only radio station, Congleton Radio, which started broadcasting on 25 June 2022.[53][better source needed]

Sport

[edit]Rugby union

[edit]Congleton is home to the third oldest rugby union club in the country, dating back to 1860. Currently fielding a mini and junior section and three adult sides,[54] the club held the world record for the longest continuous game of rugby ever played, at 24 hours, 30 minutes and 6 seconds. The club has also pioneered the development of 'walking rugby' for more senior players and has re-established a ladies' team, having previously had two of its women players represent England.[citation needed]

Football

[edit]The local football team, Congleton Town F.C., known as the Bears, play in the Northern Premier League First Division West. Their ground is at Booth Street.

Tennis

[edit]Congleton Tennis Club, one of the oldest in the country (founded in 1890), have occupied the same grounds throughout their history. The club has nine courts: six all-weather courts and three with artificial grass. Four of the courts are floodlit.[55]

Basketball

[edit]Congleton Grizzlies Basketball Club is the town's basketball team.[56]

Other sports

[edit]There are two cricket clubs, Congleton CC and Mossley CC. There are two golf clubs in the town—the nine-hole Congleton Golf Club, and the 18-hole parkland course at Astbury. Congleton Harriers running club meets weekly at Congleton Leisure Centre.[57] The club organises the Congleton Half Marathon.[58] A weekly 5K parkrun takes place at Astbury Mere Country Park. [citation needed]

Transport

[edit]Railway

[edit]

Congleton railway station was opened by the North Staffordshire Railway on 9 October 1848. It is situated on the Stafford-Manchester spur of the West Coast Main Line.[59] There is generally an hourly stopping service between Manchester Piccadilly and Stoke-on-Trent, fewer on Sundays (every 2 to 3 hours), with trains operated by Northern Trains.

The Biddulph Valley line used to terminate in the town. The railway ran from Stoke-on-Trent to Brunswick Wharf, in the suburb of Buglawton. Passenger services ended in 1927,[60] with freight services continuing until 1968 when the line was closed.[60]

Buses

[edit]Congleton is served by eight bus routes, operated by D&G Bus and Hollinshead Coaches; there are no services on Sundays. Destinations include Alsager, Macclesfield, Crewe and Newcastle.[61]

Roads

[edit]Congleton is 7 miles (11 km) east of the M6 motorway, connected by the A534. It is on the A34 trunk road between Stoke-on-Trent and Manchester, and the A54 to Buxton and the Peak District. The A536 links the town with Macclesfield, with the A527 linking the town to Biddulph and providing an alternative route to Stoke-on-Trent.

Waterways

[edit]

The Macclesfield Canal, completed in 1831, passes through the town. It runs 26 miles (42 km) from Marple Junction at Marple, where it joins the Upper Peak Forest Canal, southwards (through Bollington and Macclesfield), before arriving at Bosley. Having descended the 12 Bosley Locks over the course of about a mile (1.6 km), the canal continues through Congleton to a junction with the Hall Green Branch of the Trent & Mersey Canal at Hall Green. The canal is renowned for its elegant roving bridges.[citation needed] Congleton is one of few places in Britain where a road, canal and railway all cross each other at the same place.[citation needed]

Air

[edit]The nearest airport to the town is Manchester Airport, 20 miles (32 km) away.

Public services

[edit]Policing in Congleton is provided by Cheshire Constabulary. The main police station is on Market Square.

Statutory emergency fire and rescue service is provided by the Cheshire Fire and Rescue Service. Congleton Fire Station is on West Road, near the centre of town.

Congleton has a small Non-Accident and Emergency hospital, Congleton War Memorial Hospital, which was built by public subscription in 1924. The town is also served by Leighton Hospital in Crewe, Macclesfield District General Hospital and the University Hospital of North Staffordshire in Stoke-on-Trent.

Religion

[edit]

The four Anglican churches in Congleton (forming a partnership in the All Saints Congleton parish[62]) are:

- St John's

- St Stephen's

- St Peter's

- Trinity

Congleton Town Council lists eleven other places of worship in the town:[63]

- Congleton Community Baptist Church[64]

- Brookhouse Green Methodist Church[65]

- New Life Church[66]

- Congleton Pentecostal Church[67]

- Rood Lane Methodist Church

- Congleton Spiritualist Church[68]

- St James' Anglican Church

- St Mary's Roman Catholic Church[69]

- Trinity Methodist Church

- Congleton United Reformed Church[70]

- Wellspring Methodist Church

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons)

Historically, Congleton has seen a wide range of Christian church denominations.

- The Friends' Meeting House closed in 1741.[71]

- The Wesleyan Methodist Trinity Chapel, in Wagg Street, was founded in 1766 and was rebuilt in 1808 and again in 1967; the Primitive Methodist Chapel was built in 1821 on Lawton Street, and rebuilt in 1890 on Kinsey Street; the Countess of Huntingdon's Connexion Methodist chapel was founded in 1822; the Congleton Edge Wesleyan Methodist Chapel was built in 1833 and rebuilt in 1889; the Wesleyan Methodist Chapel in Brook Street was built in 1834; the New Connexion Methodist Chapel in Queen Street was built in 1836 and closed in 1969; the Primitive Methodist Chapel in Biddulph Road was built in 1840; the Wesleyan Methodist Chapel in Rood Lane was founded in 1861 and rebuilt in 1886.[71]

- The Unitarian Chapel in Cross Street was founded in 1687 near the Dane Bridge and in 1733 moved to Cross Street, with the present building constructed in 1883 and closed in 1978.

- The United Reformed Church (Independent/Congregationalist) was built in 1790 on Mill Street, and then rebuilt in 1876 on Antrobus Street.[71]

Education

[edit]Primary schools

[edit]- Astbury St Mary's C of E School[72]

- Black Firs Primary School[73]

- Buglawton Primary School[72]

- Daven Primary School[74]

- Havannah Primary School[75]

- Marlfields Primary Academy[76]

- Mossley CE Primary School[72]

- St Mary's Catholic Primary School[77]

- The Quinta Primary School[72]

High and secondary schools

[edit]Special and alternative schools

[edit]Notable people

[edit]

Public service and commerce

[edit]- Saint Margaret Ward (died 1588), the "pearl of Tyburn", English Catholic martyr[82] executed during the reign of Elizabeth I for assisting a priest to escape from prison[83]

- John Bradshaw (1602–1659), judge,[84] sat as President of the High Court of Justice for the trial of King Charles I, Mayor of Congleton 1637–1638

- John Whitehurst (1713–1788), clockmaker[85] and scientist, member of the Lunar Society

- Sir John Parnell, 2nd Baronet (1744–1801), Anglo-Irish Member of Parliament,[86] his family originally migrated to Ireland from Congleton

- Robert Hodgson (1773–1844), priest, Dean of Carlisle

- Gibbs Crawfurd Antrobus (1793–1861), diplomat and politician,[87] long-established family in Congleton

- Hewett Watson (1804–1881), phrenologist, botanist and evolutionary theorist

- William Newton (1822–1876), trade unionist, journalist and Chartist

- Dennis Bradwell (1823–1897), silk mill owner and Mayor of Congleton 1875–1878.[88]

- Elizabeth Wolstenholme (1833–1918), suffragist, essayist and poet[89]

- Rear-Admiral Gerald Cartmell Harrison (1883–1943), Royal Navy officer[90] and cricketer[91]

- Theodora Turner (1907–1999), born in Congleton, nurse[92] and hospital matron.

- Frank Kearton, Baron Kearton (1911–1992), life peer, scientist and industrialist

- George Harold Eardley[93](1912–1991), received the Victoria Cross[94] in 1944[95]

- John Blundell (1952–2014), Director General[96] at the Institute of Economic Affairs

- Dawn Gibbins (1961–2022)[97] entrepreneur,[98] started flooring company Flowcrete with her father.

- Sir Thomas Reade British Army Officer and Napoleon's Jailer.[99]

- Sarah Alison Russell[100] MP for Congleton constituency since 5 July 2024.

Arts

[edit]- Alan Garner (born 1934), novelist best known for his children's fantasy novels

- Louise Plowright (1956–2016), actress

- Emma Bossons (born 1976 in Congleton), ceramic artist and designer for Moorcroft Pottery[101]

- Jackie Oates (born 1983 in Congleton), folk singer and fiddle player

Sports

[edit]- Tommy Clare (1865–1929), international footballer (right-back) and football manager[102]

- William Yates (1880–1967), racewalker, competed at the 1912 Summer Olympics[103]

- Hugh Moffat (1885–1952), footballer, played for Burnley F.C. and Oldham Athletic F.C.

- Bill Fielding (1915–2006), goalkeeper for Cardiff City, Bolton Wanderers and Manchester United

- Ann Packer (born 1942) and Robbie Brightwell (1939–2022),[104] husband-and-wife Olympic gold medal athletes

- Ian Brightwell (born 1968), former Manchester City footballer with 464 club caps; grew up in Congleton

- Laura Newton (born 1977), cricketer[105]

- Tim Brown (born 1981), New Zealand international footballer, born in Congleton

- John Gimson Olympic Sliver Medallist, lives in Congleton.[106]

Twin towns – sister cities

[edit]Congleton is twinned with:

Aldermen/Alderwomen and Freeman

[edit]The following is a list of people who have been either an Alderman/Alderwoman or Freeman of Congleton, and when the title was bestowed.

- A.J. Solly (Alderman ???)[108]

- Solly (Alderman ???)[109]

- Ernest Hancock (Alderman ???)[110]

- J.A. Clayton (Alderman ???)[111]

- John Smith (Alderman ???)[112]

- Massie Harper (Alderman ???)[113]

- Harold Burns (Alderman ???)[114]

- H.W. Howard (Alderman ???)[111]

- W.I. Fern J.P. (Alderman ???)[115]

- S. Maskery (Alderman ???)[116]

- Fred Jackson (Alderman ???, Freeman ???)[117]

- Frederick Barton (Alderman ???)[118]

- D. Charlesworth (Alderman ???)[119]

- W.H. Semper (Alderman ???)[119]

- R.A. Daniel (Alderman ???)[120]

- S. Moores (Alderman ???)[120]

- A. Gleeson (Alderman ???)[120]

- Jackson JP (Alderman ???)[121]

- F Jackson (Alderman???)[122]

- Shepard (Alderman ???)[123]

- Wright (Alderman ???)[123]

- Isaac Salt (Alderman ???)[123]

- M. Pass (Alderwoman 1937)[124]

- Frank Dale (Alderman 1938)[120]

- G. Rowell (Alderman November 1945)[125]

- W. Newton (Alderman November 1945)[125]

- W.F. O'Reilly (Alderman November 1945)[125]

Freedom of Congleton

[edit]The following is a list of people who have had freedom of Congleton and when the freedom was bestowed.

- S. Maskery (Freedom of the Borough of Congleton early 1900s)[116]

- W.L. Fern (Freedom of the Borough of Congleton 14 May 1934)[126]

- W. I. Fern (Freedom of the Borough of Congleton 14 May 1934)[115]

- Frank Dale (Freedom of the Borough of Congleton October 1953)[120]

- Harry Williams (Freedom of the Borough of Congleton October 1953)[120]

Awards

[edit]

The following is a list of awards the town of Congleton has won and the year the awards were won.

- Civic Pride award (1997)

- Civic Pride Competition (1999)

- Civic Pride Competition (2001)

- Community Pride (2006)

- Community Pride (2007)

- Little Gem (2011)

- Community Pride (2011)

- Community Pride (2012)

- Best Kept Village (2018)

- Best Kept Village Overall Winner (2018)

Gallery

[edit]-

Bluebells at Dane-in-Shaw Brook SSI

-

Daneside Theatre in March 2022

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Congleton (Parish): Key Figures for 2021 Census". ONS. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ^ Ekwall, Eilert (1936). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-Names (Fourth, 1984 Reprint ed.). Oxford. p. 120. ISBN 0-19-869103-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g "The History of Congleton". Congleton Museum. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ^ "The Domesday Book Online". Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ^ "Congleton Bear Lyrics". Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 9 August 2007.

- ^ "John Tams information". Archived from the original on 19 August 2007. Retrieved 9 August 2007.

- ^ "Photographs of Congleton, Cheshire, England, UK". thornber.net. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ Callandine, Anthony (1993). "Lombe's Mill: An Exercise in reconstruction". Industrial Archaeology Review. XVI (1). Maney Publishing. ISSN 0309-0728.

- ^ Fustian Mills Talk Archived 3 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine Lyndon Murgatroyd 2007

- ^ Stephens, W. B. (1970). History of Congleton: Published to Celebrate the 700th Anniversary of the Granting of the Charter to the Town. Manchester University Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-7190-1245-7 – via Google Books.

- ^ Historic England. "WATER TOWER ON TOWER HILL TO NORTH OF WEST ROAD (1130486)". National Heritage List for England.

- ^ Pevsner, Nikolaus; Hubbard, Edward (1 March 1971). Cheshire. Yale University Press. pp. 184–5. ISBN 978-0-300-09588-3 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Book the Town Hall – Congleton Town Council". congleton-tc.gov.uk.

- ^ Alcock, Joan P. (30 June 2003). History and Guide Congleton. Stroud: Tempus Publishing Ltd. p. 87. ISBN 0752429469.

- ^ "Marie Hall Home / Danesford School, Congleton, Cheshire". www.childrenshomes.org.uk. Retrieved 6 October 2024.

- ^ Historic England. "DANESFORD SCHOOL (NATIONAL CHILDRENS HOMES) (1130481)". National Heritage List for England.

- ^ "Congleton Elects Its First Lady Mayor". Congleton Chronicle. 16 November 1945. p. 7.

- ^ Alcock, Joan P. (30 June 2003). History and Guide Congleton. Stroud: Tempus Publishing Ltd. p. 104. ISBN 0752429469.

- ^ "Princess happy to extend vist". Evening Sentinel. 6 October 1983. p. 13. Retrieved 17 June 2023 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Congleton Welcomes The Prince of Wales & The Duchess of Cornwall". Congleton Town Council. 25 January 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ^ Dodd, Vikram (6 December 2019). "Joseph McCann guilty of horrific rapes after being freed by mistake". The Guardian. London. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ^ Watterson, Kaleigh (31 March 2022). "Town appoints ale taster as part of 750th celebrations". BBC News. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ Brown, Mark (31 March 2022). "Here for the beer: Congleton appoints ale taster for town anniversary". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ Rack, Susie (29 September 2023). "Market revival aims to redefine town centre". BBC News. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- ^ "Market Quarter plans for future expansion". Congleton Chronicle. 25 April 2024. p. 4.

- ^ Porter, Gary (14 December 2024). "Plans for next phase of town's 'Market Quarter' regeneration unveiled". Stoke Sentinel. Congleton.

- ^ Walker, Melanie (3 October 2024). "Oyez! Town has a new (female) voice". Congleton Chronicle. p. Front Page.

- ^ Watterson, Kaleigh (5 July 2024). "Historic wins for Labour in Cheshire". BBC News. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

- ^ "Your Councillors". Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ "Town Council". Archived from the original on 13 February 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- ^ "History – Congleton Town Council". congleton-tc.gov.uk. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ Stubbs, Gill (26 April 2011). "Myths and Legends of Cheshire: PRIESTY FIELDS, CONGLETON". Myths and Legends of Cheshire. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ Congleton Transport Development Plan (PDF). Cheshire East Council. May 2022. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 July 2022. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ "Heritage – Berisfords Ribbons". berisfords-ribbons.co.uk. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ "Billiard and Snooker Heritage Collection – Billiards & Snooker balls". snookerheritage.co.uk. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- ^ "Technical Information – Balls – Titan Sports & Games". titansports.co.uk. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- ^ "Little Moreton Hall". cheshirenow.co.uk. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ "Astbury Mere Country Park". alsager.com. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ "Cheshire East Council – Astbury Mere Country Park". Archived from the original on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ "Daneside Theatre". danesidetheatre.co.uk. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ "Welcome to Congleton Museum". congletonmuseum.co.uk. Archived from the original on 26 December 2005.

- ^ "Congleton Food and Drink Festival". foodanddrinkfestival.net. Archived from the original on 11 April 2009. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ^ "Congleton Pride". congletonpride.co.uk. Archived from the original on 9 July 2020.

- ^ "What goes into creating Congleton's music festivals?". Congleton Chronicle. 31 August 2023. p. 16.

- ^ "Pride invites firms to sponsor 2023 event". Congleton Chronicle. 27 April 2023. p. 4.

- ^ "Congleton Carnival – A History – Congleton Heritage Festival". congletonheritagefestival.com. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ a b "Bearmania – 2011 The Congleton Year of the Bear!". Congleton Partnership. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ Bounds, Andrew (15 September 2011). "Congleton: Bearmania puts market town on the map". Financial Times. London. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ "Full Freeview on the Winter Hill (Bolton, England) transmitter". UK Free TV. May 2004. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ^ "Freeview Light on the Congleton (Cheshire East, England) transmitter". UK Free TV. May 2004. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ^ "About Us". Beartown FM. Archived from the original on 25 May 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ "Congleton Radio launches tonight Saturday 25th of June at 7pm". Congleton Radio. Retrieved 4 August 2022 – via Facebook.

- ^ "Teams". Congleton RUFC. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ "About Us". Congleton Tennis Club. 2022. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ "First national basketball league games for Grizzlies". Congleton Chronicle. 26 September 2024. p. 41.

- ^ "About Us". Congleton Harriers. Archived from the original on 23 June 2016. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ "Congleton Half Marathon". Congleton Harriers. Archived from the original on 31 August 2016. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ "Congleton Station Information". northernrailway.co.uk. Archived from the original on 16 July 2017. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- ^ a b "Activities and Information About the Biddulph Valley Way". Chesire East Council. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- ^ "Congleton – bustimes.org". bustimes.org. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ "New name for parish of Congleton as church looks to the future". Congleton Chronicle. 28 July 2022. p. Front Page.

- ^ "Places of Worship". Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ^ "Congelton Baptist Church". Archived from the original on 6 January 2013. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ^ "The Methodist Church – Dane and Trent Circuit". Archived from the original on 5 January 2013. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ "New Life Church". Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ "Cross Street". Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ "Congleton Spiritualist Church". 2011. Archived from the original on 28 August 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ "St Mary R C Church". St Mary R C Church. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ "Minshull Vernon United Reformed Church". 2013. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ a b c "Congleton". genuki. 1996–2012. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Schools in the Borough". Congleton Borough Council. Archived from the original on 14 June 2006. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- ^ Yates, Jay (27 April 2023). "Show goes on for actor who followed his dreams". Congleton Chronicle. p. 27.

- ^ "Launch of new family hub in the town centre". Congleton Chronicle. 7 December 2023. p. 40.

- ^ Greensmith, Alex (14 February 2023). "£1000 mental health boost to Congleton primary school". Congleton Nub News. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ Connolly, James (30 March 2023). "Ofsted condemned after teacher's death". Congleton Chronicle. p. 5.

- ^ "Extracts from the Chronicle Files "10 years ago"". Glancing Back. Congleton Chronicle. 1 December 2022. p. 6.

- ^ "Another 'good' Ofsted is 'fair assessment'". Congleton Chronicle. 23 March 2023. p. 40.

- ^ Greensmith, Alex (9 December 2022). "Congleton: Former Eaton Bank pupils raise thousands for cancer charity". Congleton Nub News. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ "Aidenswood School – GOV.UK". get-information-schools.service.gov.uk. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ "Expanding specialist school records a loss". Business News. Congleton Chronicle. 18 July 2024. p. 10.

- ^ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: St. Margaret Ward". newadvent.org.

- ^ "'Pearl of Tyburn stood for what she believed'". Congleton Chronicle. 29 August 2024. p. 14.

- ^ Lee, Sidney (1886). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 06. p. 178-181.

- ^ Carlyle, E.I. (1900). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 61. p. 108-109.

- ^ "PARNELL, Sir John, 2nd Bt. (1744-1801), of Rathleague, Queen's Co. | History of Parliament Online". historyofparliamentonline.org.

- ^ "ANTROBUS, Gibbs Crawfurd (1793-1861), of Eaton Hall, nr. Congleton, Cheshire and 11 Grosvenor Square, Mdx. | History of Parliament Online". historyofparliamentonline.org.

- ^ Stephens, W. B. (1970). History of Congleton: Published to Celebrate the 700th Anniversary of the Granting of the Charter to the Town. Congleton: Manchester University Press. p. 151. ISBN 9780719012457 – via Google Books.

- ^ "'Our Elizabeth' cemented in town's history". Congleton Chronicle. 16 March 2022. Archived from the original on 17 March 2022. Retrieved 13 March 2023.

- ^ Catalogue description

Name Harrison, Gerald Cartmell

Date of Birth: 8 October 1883

Rank: ... United Kingdom National Archives. 15 May 1898. - ^ "Gerald Harrison Profile – Cricket Player England | Stats, Records, Video". ESPNcricinfo.

- ^ "Obituaries: Theodora Turner". The Independent. 31 August 1999. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- ^ Alcock, Joan P. (30 June 2003). History & Guide Congleton. Stroud: Tempus Publishing Ltd. p. 95. ISBN 0752429469.

- ^ "No. 36870". The London Gazette (Supplement). 29 December 1944. p. 139.

- ^ "George Harold Eardley". victoriacross.org.uk. Archived from the original on 27 May 2012.

- ^ ATLAS NETWORK, 22 July 2014, IN MEMORIAM: JOHN BLUNDELL (1952–2014) retrieved December 2017

- ^ Watson, Laura (15 February 2022). "Tributes as 'secret millionaire' Dawn dies after 30 years of business brilliance". Stoke Sentinel. Archived from the original on 15 February 2022. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ Coventry, Laura (7 January 2011). "Appearance on Secret Millionaire inspired me to change direction in life, reveals entrepreneur Dawn Gibbins". Daily Record. Archived from the original on 14 February 2018.

- ^ "Extracts from the Chronicle Files "10 years ago"". Glancing Back. Congleton Chronicle. 11 July 2024. p. 6.

- ^ "Sarah Russell". www.congletonlabourparty.co.uk. Retrieved 29 July 2024.

- ^ Walker, Melanie (9 March 2023). "Potter is 'honoured' to be Throw Down judge". Congleton Chronicle. p. 14.

- ^ SoccerBase Database retrieved December 2017

- ^ "William Yates Bio, Stats, and Results". Olympics at Sports-Reference.com. Archived from the original on 18 April 2020.

- ^ "Remembering Robbie Brightwell". Team GB. 7 March 2022. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ ESPN cricinfo Database retrieved December 2017

- ^ Bottomley, Lee (27 September 2023). "Olympians claim Irish Sea sailing record". BBC News. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ^ "Les jumelages". trappes.fr (in French). Trappes. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ "Extracts from the Chronicle Files "100 years ago"". Glancing Back. Congleton Chronicle. 9 December 2021. p. 6.

- ^ "Extracts from the Chronicle Files "100 years ago"". Glancing Back. Congleton Chronicle. 26 September 2024. p. 6.

- ^ Alcock, Joan P. (30 June 2003). History & Guide Congleton. Stroud: Tempus Publishing Ltd. p. 100. ISBN 0752429469.

- ^ a b "Chronicling the past

Bringing old characters to life". Congleton Chronicle. 8 February 2024. p. 27. - ^ Alcock, Joan P. (30 June 2003). History and Guide Congleton. Stroud: Tempus Publishing Ltd. p. 115. ISBN 0752429469.

- ^ "Remarkable family with local link". Congleton Chronicle. 9 June 2022. p. 7.

- ^ "BY-PASS YES,

BUT MAYOR

HAS MIXED

FEELINGS". Evening Sentinel. 30 August 1972. p. 12. Retrieved 25 June 2023 – via Newspapers.com. - ^ a b "* DAY BY DAY *". Evening Sentinel. 15 May 1934. p. 6. Retrieved 25 June 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "CONGLETON'S

"GRAND

OLD MAN."

79th Birthday of

Ald. S. Maskery.

SEVEN TIMES MAYOR". Evening Sentinel. 4 September 1931. p. 3. Retrieved 25 June 2023 – via Newspapers.com. - ^ "Honouring Congleton Public Men". Evening Sentinel. 8 October 1953. p. 2. Retrieved 19 October 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "ANOTHER ALDERMAN RESIGNS". Congleton Chronicle. 9 November 1945. p. 1.

- ^ a b "Thrilling start to Royal tour with 'meet the people' stroll". Evening Sentinel. 5 May 1972. p. Front page. Retrieved 25 June 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f "HONORARY FREEDOM OF THE BOROUGH". Staffordshire Weekly Sentinel. 30 October 1953. p. 4. Retrieved 25 June 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Extracts from the Chronicle Files "100 years ago"". Glancing Back. Congleton Chronicle. 17 August 2023. p. 6.

- ^ "Extracts from the Chronicle Files "100 years ago"". Glancing Back. Congleton Chronicle. 15 August 2024. p. 6.

- ^ a b c "CONGLETON TOWN COUNCIL

ALDERMANIC SEAT VACANT". Evening Sentinel. 4 September 1931. p. 3. Retrieved 11 April 2024 – via Newspapers.com. - ^ Stevans, W.B., ed. (1970). History of Congleton

Published to Celebrate the 700th Anniversary of the Granting of the Charter to the Town. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-7190-1245-7 – via Google Books. - ^ a b c "Three new Aldermen". Congleton Chronicle. 11 November 1945. p. 8.

- ^ "Freedom of Congleton". Evening Sentinel. 15 May 1934. p. 10. Retrieved 25 June 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

Sources

[edit]- Head, Robert (1887). Congleton Past and Present. Robert Head.

External links

[edit]- Congleton Town Council website

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Congleton Museum – local history museum and education resource